Antoine

Cosse's newest book, Harold,

published through Retrofit/Big Planet, is one of those books that

requires multiple readings in order to … not so much understand

really, but feel comfortable with. There is a preponderance of

narratives weighing heavy in this book, each one somehow playing into

and off of the other, but none of them are fully complete in terms of

closure.

Which,

of course, can be frustrating as much as it can fascinating. And

that's the thing with a book like Harold. It makes you examine

yourself as a reader as much as it makes you examine what you're

reading.

Retrofit's

solicitation for Harold

doesn't help much in unpacking things. It reads:

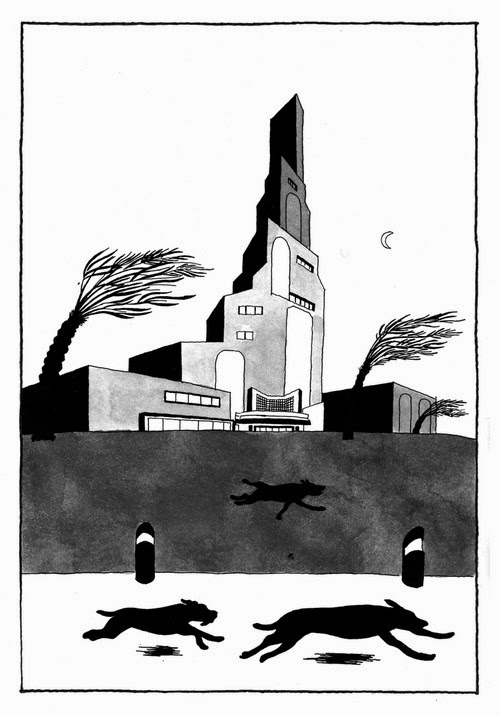

As

packs of wild dogs roam through a quiet city, a mysterious man and

his hulking driver Harold wait outside a luxury hotel. When their car

is surrounded by paparazzi looking for a princess staying at the

hotel, Harold begins to tell the tale of the rebellion against the

princess's father. Mysteries of the past slowly unfold against the

strangeness of their present.

So

yea... that.

Harold

is the kind of book that forces questions of intent as much as it

raises concerns about choices. Everything is thick with possibility

in the book, yet resolution is only to be found in the pages Cosse

hasn't drawn.

Here's

a small sampling of the notes I took while reading through Harold the

first time:

- Why are there packs of wild dogs in negative and positive space?

- What is the plausibility of the architecture?

- Why is the man wearing a tuxedo?

- Why does he need a bodyguard?

- Why does Harold wear the mask over his mouth?

- Why are the paparazzi anthropomorphic animals?

- Why the repetition of forms?

- What happens one floor down?

- Does it actually hurt to smoke through the masks?

See

what I'm doing here? I'm creating a Whitman-esque poem listing

questions that Harold's

narrative refuses to answer. Frustrating? Yes. Interestingly enough,

though, in the face of so many enigmatic quandaries, a reader's

response to the book depends almost entirely on how he or she value

him or herself.

If

you lack confidence in your reading, then you're to blame for

Harold's

infrangibility. Alienated by your own lack of understanding, you feel

shamed and shaken – you cast the book aside with a teenager's sulk

and call it “stupid” while petulantly stamping your feet.

If

you feel adroit in unpacking difficult texts and you still find

Harold

tight in its grip on its mysteries, then you skew your sideways

glance at Cosse himself. You sit in your chair by the fire and, while

rubbing your belly, use multisyllabic words to hurl biting diatribes

at his failure as an artist.

So

much of our world is built around our own sense of self. We enter

experiences with selfish aspirations.

But

maybe this resignation and blame is besides the point. Maybe the

pointlessness is the point.

Is

there equivocation in admitting that unintelligibility is sometimes

precisely what is necessary for what the artist wants to convey? Are

there times when in order to clearly communicate a theme, the artist

must eschew explicitness and exactitude?

I'm

fairly certain you've seen it before. I know that I have.

Back

in July of 2012, my friend Keith Silva and I went around the bend on

this issue as we tried to figure out meaning in David Hine and Shaky

Kane's BulletproofCoffin: Disinterred

and my panic and his assurances warrant a revisit in the context of

examining Harold.

In

the course of writing about Bulletproof

Coffin: Disinterred, I

had panicked because I couldn't wrap my head around what Hine and

Kane wanted me to grok. Silva called these artists “perennial

expectation deflectors, subversives of subversions”

operating in a realm of “no

truth, only subversions of subversions and that kind of thing is as

unsettling as it is uncanny.”

Which,

come to think of it, did little to assuage my panic...

While

Hine and Kane were tilting at the windmills of comic books past and

painting pages with the goo of post-post whatever it is that we've

moved past already, Cosse, in Harold,

is working from a different set of influences – more Truffaut and

Chabrol then Ditko and Kirby – so this concept of subversions of

subversions has its place, I suppose. It's just transferring the

medium and therefore putting up more walls to comprehension as it

tickles the anus of expectations.

Later

in that review of Bulletproof

Coffin,

Silva then had the audacity to suggest that not everything has to be

clear to carry meaning, that perhaps we see best through an opaque

lens. He wrote, “it's

not supposed to make sense. Why should it? I like order as much as

the next dude, but messiness, like it or not, makes life worth living

... somebody's got to straighten crooked pictures in hotel rooms,

after all.”

Yea

– I get all that. Over time we become blind to the familiar –

sometimes we need something sui

generis

in order to regain our sight. “Easy

is static; creation is dynamic,”

I said.

Following

this train of thought, last night Comics Bulletin publisher Jason

Sacks said to me something along the lines of how the absence of a

traditional narrative structure not only makes you work harder

towards understanding, it also allows a story's emotional resonance

to step to the forefront. Perhaps this was Cosse's plan?

Yet

the emotional weight of Harold lies mostly in its insouciance.

Its indifference manufactures a yearning of sorts, the sense of

something lost and the longing for either its return or something

better to replace it. But the lack of beginnings and endings to its

multi-layered narrative makes whatever that thing is or those things

are purely a matter of speculation, as if all the signposts are there

to guide you, you just cannot penetrate the language.

So

where does that leave the reader and, more importantly for my

purposes now, the critic? Of course there is that liminal state

between knowledge and inability, between logic and emotion, between

appreciation and repulsion, but it is truly an uncomfortable place to

inhabit. The fact that Harold has brought me to this place

bears note as much as it does merit.

Fundamentally,

Antoine Cosse is playing a chess game with a book like Harold.

He's relying heavily on your sense of personal value, as much as he

is his abilities as an artist. This is a complicated book masked as a

simple, though beseeching story. Cosse plays with negative and

positive space in order to reflect the duality of your own substance.

He sets loose all the wild dogs to chase and devour who you think you

are.

Harold

plays an off-kilter funk to the rhythms of your prehension – or

lack thereof – and demands either you dance or get off the floor.

And

that, perhaps, is its intrinsic value. Art gets you gamboling one way

or another.

You

can pick up a copy of Harold from Retrofit here.

No comments:

Post a Comment