When reading through Haze, the most apparent thing is the blending of shape and color. The romantically entwined protagonists, Wade and Finn, are two high school students with a shared passion for swimming. The comic begins and ends with scenes involving the two boys in water, either in an ocean, in a swimming pool, or a bath. Complimenting this focus on water, Haghighi’s sketchy penciling blends landscapes and atmospheres, create a pleasantly loose, liquid tone throughout the book.

This use of water as a central theme acts as a reflection of the seemingly fluid nature of Wade and Finn’s relationship. Haze captures their relationship as not being set in stone. Instead, it’s shown as being in motion, traversing from the pair half-acknowledging their feelings for each other to, later, relinquishing the pretense of pretending and admitting their desire to become a couple. The climactic actions in the comic’s final few pages that enable the pair to be together act almost as a dam bursting, a wave of emotions pouring out.

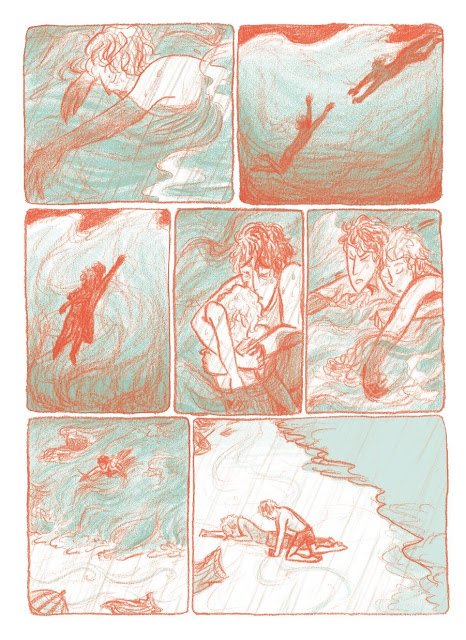

Countering this fluidity is the comic’s panel structure. Often, the characters and their actions are condensed into compact panels which gives the otherwise free-wheeling feel of Haze a welcome sense of confinement. Panels large and small still make room for Haghighi’s swirling art, whose gorgeous, rippling nature comes into contact with everything and everyone featured in Haze, fashioning a cohesive visual voice.

Fractured love is the other chief theme of Haze, and this provides a darker, more stern alternative to the otherwise playful attitudes Finn and Wade have for each other. In contrast to Haze’s emphasis on color and shape, the dialogue in the comic is minimal and vague. Fortunately, Haghighi flexes her narrative muscles in these moments and what precious little dialogue there is does a great deal in telegraphing not only the disconnect between Wade and Finn but also their desire to reconnect.

The actual story of the comic is equally fragmented. Haze’s narrative is less of a complete story, and more of a series of interlinked scenes, snapshots of a relationship that has withered to some extent but eventually blossoms into something more unified. The pacing feels rough, the scenes occasionally bolted on, but the payoff is well received. The aforementioned skeletal use of dialogue ends up complimenting this narrative structure well. These loosely connected scenes aren’t cluttered by clumps of dialogue and action. Haze’s brief page run reflects Haghighi’s ambition, opting to portray a relationship neither at the beginning or the end, but rather, caught in the middle.

Bonding these scattershot scenes together is Haghighi’s supremely warm artwork. The colors, chiefly composed of a red and blue palette, bear an almost nostalgic quality, the warmth exuding from the pages rise like the temperature on a hot summer’s day, inviting the reader in. There’s a great emphasis on colors as a communicator of emotion

Haghighi primarily uses reds to shade in the characters and blues to illustrate nearly everything else. The shades of red that illuminate Wade and Finn highlight their warmth for each other and the romantic tension between the pair. It’s a subtle bit of business that underscores the tenor of their relationship. Haghighi also expertly uses a colder shade of blue to indicate a series of hallucinogenic flashbacks Wade experiences throughout the comic to rosier days spent in Finn’s arms. This darker blue emphasizes the coldness Wade feels, isolated from Finn and his initial lack of confidence regarding how to amend their relationship.

The story itself buckles somewhat in Haze’s climactic scenes. Throughout the comic, Wade’s flashbacks increase in their severity, culminating in the comic’s final, action-packed scene. The decisive moment in Haze that brings the two back together comes when Wade believes he sees Finn diving into a stormy ocean during a beach party and dives in after him. Seeing Wade make a seemingly odd venture into the sea, Finn pursues him, eventually rescuing Wade from drowning.

It’s a sweet scene that breaks down the emotional barriers the pair have created against each other earlier in the story, but it’s communicated in a jarring manner. There’s no hint given that what Wade witnesses is nothing more than a false vision. The ensuing drama that swells from the duo diving in to rescue one another is nimble and heartfelt, it’s just that Wade’s triggering of these events feels rushed and jumbled. This perhaps highlights the weaker points of Haze’s brief, scattershot structure and suggests how scenes such as these would benefit from a longer length to allow such scenes to breathe.

Still, in Haze, Wade and Finn serve as the glue that binds all of these intricate elements together. Haghighi portrays them as an empathetic, flirtatious pair, yet hardwired with youthful vulnerability. The fondness they have for each other is juxtaposed by a seemingly self-imposed distance. It’s as if their eventual succumbing to each other marks a leap of maturity for them, with Finn telling Wade to cease with the disingenuous, casual flirting and become more open, more direct, more truthful in his feelings.

Despite some jagged narrative delivery scuppering its emotional weight, Haze is an evocative, endlessly charming affair. It’s a comic who’s appeal lies in how it shows high emotions through sharp, precise art. Story and art grow around each other with effortless care and attention to detail, and Haghighi’s depiction of a torn love that manages to rectify itself bolsters its value. Haze is an enchanting comic who’s emotionally tuned-in state makes for satisfying reading.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Fred McNamara thoroughly enjoys writing about comic books and TV shows you've never heard of. His love of indie/small press comics arose through his role as senior editor for the superhero/comic book hub A Place To Hang Your Cape. He's currently enduring a prolonged period of sleepless nights as his debut book, Spectrum is Indestructible, is gearing up for publication later this year from Chinbeard Books.