What is the function of a record? To what extent does any record – the video of a murder, a mental health survey form, a graphic novel, even – operate as a trustworthy document of reality in an age of doctored videos and fake news? If fiction teaches anything, it’s first that a deftly crafted story can sometimes feel more real than reality itself, more real than what goes on beneath the ever-darkening political cloud over contemporary America – a shadow beneath which, increasingly, all media is consumed.

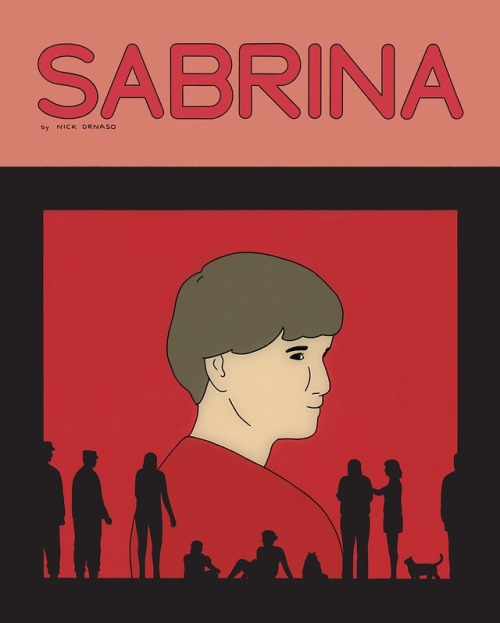

Much has been written about Sabrina, in the short span since its release – coupled with a back-cover blurb from Zadie Smith calling the book a masterpiece, expectations run high as you dive into this topical, arresting book, author Nick Drnaso’s follow-up to LA Times Book Prize-winning Beverly. Sabrina is a record of something, that much is sure. Superficially, it’s a record of the emotional fallout of the kind of highly publicized, viral violence carried out by men with Reddit manifestos against the innocent and therefore vulnerable. But beneath the surface, Sabrina is a book of implications, in both senses of the word – Drnaso is a master of suggestion, and, in many places, he implicates the reader as a member of a society that has a morbid and enduring fascination with senseless, brutal violence.

Sabrina’s visual style lies somewhere between Chris Ware’s meticulous drawings and an airplane safety pamphlet: flat colors, attenuated but uniform lines, people whose expressions rarely deviate from neutral affability. The moments when their expressions do change are leant a certain gravitas in contrast. Drnaso’s economical drawings belie the profusion of deliberate detail in Sabrina.

The book opens on its eponymous character with her sister, Sandra. Their conversation is quotidian and genial. Sabrina fluctuates between long, silent stretches of characters engaged with mundane daily tasks and authentic dialogue. The opposition of fake vs. real is introduced early and subtly in these first few pages – Sandra picks up fruit from a bowl, and remarks that she’d forgotten they were fake – Sabrina admits to repainting them. “Don’t they look real?” she asks, pleased at the tiny deception. The moment is small, and the narrative moves steadily past it, but like so many details in Sabrina, it wants us to question the potential for harm in every comfortable domestic veneer. Sandra asks Sabrina if she would accompany her on a lengthy bike trip around the Great Lakes in the coming spring. Sabrina, while drawn in by the chance to get away from the city and the internet, initially expresses some doubts about the dangers of precipitous cliffs and wild animals. Sandra counters with an anecdote about being away from home at nineteen and being stalked and sexually harassed by three men who were “out hunting”. “Don’t worry about riding a bike through the woods,” she tells Sabrina ominously, “the fucking wild animals stay in hotels.”

This statement foreshadows Sabrina’s subsequent disappearance and death at the hands of a man who lives a block away from her, but it also implies that the danger, the real danger, lies not in the natural world but rather in the fabric of American culture itself. The danger is men, men who look harmless, but like a painted ersatz apple, are not at all what they seem.

Toxic masculinity underscores everything in Sabrina – it is not insignificant that it is an innocent woman who is the victim of Timothy Yancey, a man who went on “long vitriolic rants” on MRA message boards, whose suicide note is a long list of his favorite movies, and who lived a block away from Sabrina but didn’t actually know her. In the video of Sabrina’s murder, which we never see, Yancey characterizes her death as a “means to an end” so that his voice will be heard “above the din of chatter”. “No one,” Yancey laments in the video’s preamble “is going to enjoy this less than me”. But just as for the viewers who can’t help but click on the snuff film Yancey makes, enjoyment is hardly the point.

As the news of Sabrina’s disappearance turns to the news of her death on tape, her grieving boyfriend Teddy isolates himself completely from the outside world and even from Calvin, his estranged childhood friend, host, and only companion during his private unraveling. Teddy’s sole, distorted window into the world becomes a conspiracy-theorist with a talk radio program, to the point that we wonder if he, like Yancey, will lash out randomly and violently against the duplicity and ignorance they have come to see as inherent in the outside world, lurking beneath the facade of normalcy. In a particularly brilliant set of pages, Drnaso draws a beautiful visual parallel between Calvin reaching for a doorknob and Teddy raising a knife. In both Yancey and Teddy, we witness the nadir of toxic masculinity in two men who have come to see violence as literally the only way that they can express themselves and connect – Yancey because he believes that his violent act will finally draw attention to him (as it does) and Teddy, who cannot find or imagine any place for his grief and anger at Sabrina’s pointless and horrific death.

This exploration of isolation engendered by the weird entanglements of the public and private are explored through Sandra as well. Like a teen who’d rather toss Snaps into the void than talk to a friend one-on-one, Sabrina’s sister feels more comfortable delivering her story to a crowd of strangers than talking privately with her close friend. She eventually excoriates Teddy for failing to connect to her as someone wading through the same trauma, perhaps the only person who really understands.

Calvin tries meanwhile to keep a handle on his own degenerating situation. He’s a “boundary technician” working a desk job in the air force, estranged from his ex-wife and young daughter. Each workday he fills out a mental health survey that asks him to rate his stress level and the likeliness of suicidal ideation by filling in bubbles. Drnaso takes this opportunity to explore the toxic conflation of mental illness and weakness as it relates to masculine identity. Like many men who perceive asking for help, especially with mental health issues, as an unacceptable sign of weakness, Calvin never writes on the lines below that ask him to elaborate on his answers, never asks to speak with a clinical psychologist, even when he inevitably fills out the bubbles for highest stress, lowest mood, greatest risk. Calvin and Teddy occupy the same house for most of the book, and they both grapple with depression, loss, and anxiety, but they never have a meaningful conversation about it. Drnaso conveys their states of mind through body language, long silences, a sense of building tension and desperation.

Sabrina warns us of the consequence of a toxic culture that has impressed on men that they must never connect genuinely and nonviolently with other people because there is nothing more emasculating than vulnerability. What is the function of a record? Sabrina suggests that a record exists not to tell us an absolute truth, but to give us an idea of where we went wrong. Where we looked in the wrong places for fidelity, where we sought a balm but found poison - where we might have trusted someone, talked to them, connected face-to-face, but instead we told, wrote, showed, or read a short-term, comforting lie and withdrew into ourselves. It is an unsettling, important, and painfully relevant book in 2018.

--------------------------------------------------------

Sara L. Jewell is a freelance writer, artist, comic creator, and educator based in New Jersey. You can find her at saraljewell.com or rambling on twitter @1_saraluna. All email inquiries can be sent to

No comments:

Post a Comment