Taylor Lilley: Well Elkin, if we’re going to do this I owe you the true genesis of this article. I picked up March: Book Onebecause of Nate Powell and shame. For someone as enamoured of comics as I, the opportunity to drink in some Powell and plug gaps in my Civil Rights Movement knowledge was too good to miss. Learning with a side of beauty, if you will. Around a week later I found myself in a small English town, in the only comic store for many miles around, eyeing a copy of Kyle Baker’s Nat Turner. If you’ve ever been to Bedford, you’ll know how crazy unlikely that seemed.

I was impressed by the contrast between the two book’s varieties of monochrome, and wondered whether their visual disparity reflected anything more than the artists’ inclinations. I wondered at the contrast between Nat Turner’s rear cover list of comics industry plaudits and March’s New York Times bestseller status. I couldn’t stop noodling, so I read both books over, and started listing contrasts.

Nat Turner came out in a collected, mass market friendly edition only a few years pre-Obama. March is launched in the first year of Obama’s second term. Where Nat Turner tells of a small, violent uprising against slavery’s greater brutality, its sparse narration “quoted” from the uprising’s leader, March is one man’s memoir of his part in a larger, peaceful movement. One is generally impassioned in tone, visually expressive almost to a fault, the other more measured, elegantly arranged around a through-line of resolve. One garnered Glyphs and Eisners, the other instant NYT bestseller status.

Before long, I reached the obvious conclusion. A largely silent comic culminating in infanticide will never beat a tale of idealism and non-violent struggle to the NYT’s #1 spot. March is easier to swallow, less painful to grapple with as lived experience than the rending of the Nat Turner story. Fine. So then my next question is, does March render Nat Turner obsolete?

Has history reached a remove from Turner’s rebellion that degrades its instructional value? Is John Lewis’s experience, faith-tempered but rationally directed, more useful than Nat Turner’s superhuman determinism? I don’t believe so. Nor do I believe that graphic works of the Civil Rights Movement should be bound to depict bloodshed and visceral excesses of inhumanity.

Short of a comprehensive Civil Rights Movement graphic novel reading list, where do we place these works in relation to each other for the comics reader, rather than the historian?

Elkin? Did I lose you?

Daniel Elkin: I was lost, but now I'm found. Having found my way, though, I'm not sure if we are in the same space, Lilley.

I see March and Nat Turner as a proton and an electron circling the same nucleus. While ostensibly about the same general theme of overcoming racial oppression, they are opposites in execution.

It is as if these books are polemics regarding different responses to the same inhumanity. March's message of non-violence is counterbalanced with the violence of Nat Turner's tale. It is the peaceful words of Jesus that forms the New Testament moral center of March, while the destructive force of an Old Testament angry God guides the narrative of Nat Turner. Talking vs. Action. Sitting down vs. beating down. A bus strike vs. an axe strike.

Both of these stories are important parts of the American Civil Rights Movement and they come at the idea from their own struggle's intent. I gather, though, that the larger questions you are ultimately asking are which is more effective in terms of a comic and how is each participant framed by the creators of these books?

Taylor Lilley: Precisely, Elkin, precisely! Your binaries are all on point, and that’s exactly the issue. Both stories are important, they work as counterbalances to each other, and yet you and I both know that outside of comics aficionados and those with particular diligence in their Civil Rights Movement reading, only one of these books will get read. And it will likely be March. To me that’s a loss for the Movement and for comics, for of the two March is the most like the “picture books” comics are often dismissed as. March is many things, but on a purely formal level, while accomplished, it does not advance the art of comic-making. Nat Turner is an embrace of the form, a devotion to telling a story as only comics can, and one whose story resonates more powerfully for it.

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it, right? So as the dominant narratives of various hard-won freedoms and privileges evolve, and in evolving, de-emphasise the death and horror that incited their struggles, aren’t we doing both the form that delivers those narratives, and those who died, a gross disservice?

Looking at the instant, widespread publicity and goodwill greeting the March project as compared to Nat Turner’sreception, even given the growth of the comics web, the different place the form now occupies in our culture, and the second life in libraries that Nat Turner certainly achieved, it seems the more acceptable, less formally challenging narrative seems set yet again to become dominant, while the greater work of art becomes a footnote. Cruelly ironic, since Nat Turner’s greatness as a work of sequential art is precisely what makes it so effective!

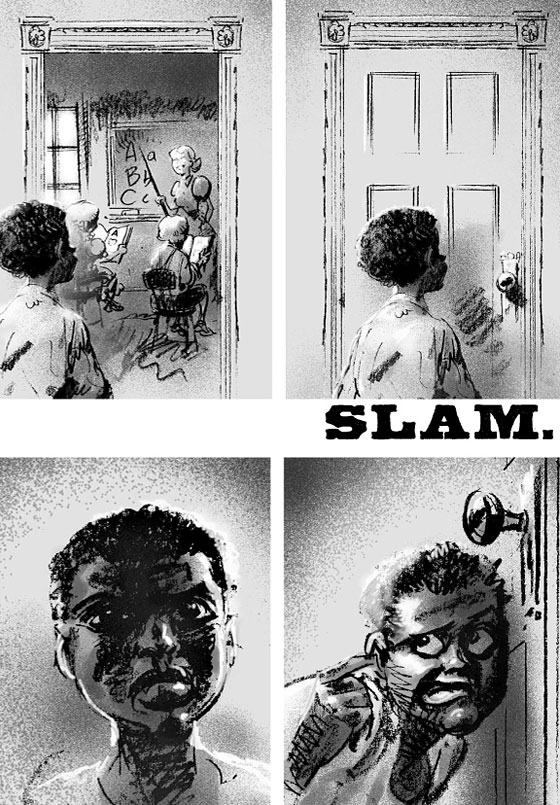

Though the separation of text and images in Nat Turner is more discrete, closer to a picture book in style, their juxtaposition is a deliberate ploy which adds tension to the reader’s experience, beyond that of the story itself. Conversely, March looks much more like a modern comic, smoothly fusing text and image, but this slickness is in service of a less challenging, recitative style of story-telling. So while I enjoyed March, and learned from it, reading Nat Turner made me then question the comfort with which March had furnished me. For isn’t the discomfort of narratives such as these part of their value? Do we not submit to these narratives to be discomfited, placed in a virtual peril from which safety allows us to learn?

Maybe this seems precious, and I’m ignoring a “gateway” argument. Perhaps March will be the book that makes people look to the comics canon for its Nat Turners (in which case they’d only have to visit Baker’s site). And it’s terrific that mainstream press is being given to coverage of a comic without a cape in sight. But this seems another example of comics as a “cool” delivery system, rather than the medium being chosen for its unique capabilities.

Elkin: The use of comics as a “cool” delivery system has been something I've been thinking about for some time. The idea that people force a narrative into a comic book to capitalize on the supposed hipness of the medium does a disservice to both the story and comics themselves. How many comics have I come across that were obviously failed screen-plays – the creator couldn't get the film made so, instead, they hopped aboard the new hotness of comics in order to get their story out there (for much less expense, but at what price)?

Then there is the issue of “comics journalism” – another genre that makes me question intent. Is this really comics? Do words and art function together simultaneously in order to tell the story, do both aspects need one another in order to convey the emotional and thematic heft of the narrative? Or is this just capitalizing on an expanding market? Are the books of, for example, Joe Sacco really comics, or are they another thing all together? And perhaps this is fundamentally where you are going with your questions, Lilley.

But before we lace up our boots and hike through that discussion, I do want to talk a little more about the differences between March and Nat Turner in terms of your idea of “only one of these books will get read,” and this has to do with the basic story behind each. In my mind, the popularity behind March compared with Nat Turner has more to do with the idea that March is the narrative of the Civil Rights struggle that everyone wants. Both sides of the argument are much more comfortable with the non-violent resistance tale. It works better as mythos, and it therefore settles more easily in our own conceptions of history. The protagonists in this are clean, the struggle more noble, the cause more clear. Turner's story is filled with grey areas (covered in blood). His religious mysticism and the violence it engendered makes making him heroic, if he even is heroic, that much murkier.

And this is what makes Nat Turner the better comic, in my opinion. There's nothing clean about this book. Baker uses the tricks of “comic booking” in order to infuse his telling with emotional intensity, and it is within the inherent areas of moral relativism that the book derives its intensity. Words and pictures, though separated cleanly in the presentation, DO work in concert to drive the narrative. Turner's words are enhanced by Baker's art, and vice-versa. This dualism, alas, is not so harmonious in March. March would function as well, if not better, as a straight prose piece; Powell's beautiful art does little to complement the story, it only seems to echo it.

Lilley: Before we get too far into decrying the exploitation of comics for their cool, we should probably acknowledge thatMarch has another reason to take this form. Lewis explicitly references the 1958 publication of Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, a ten cent comic which spread word of Dr King’s philosophy, and of his involvement with the Rosa Parks inspired bus boycotts of 1955. So it can be argued that there’s a legacy connection between comics and the Movement that predates current cool, an ennobling legacy of comics as a more accessible and therefore more effective medium than books.

This heritage, especially when combined with the recent spate of studies proving the potency of comics as an educational tool (a purpose clearly intended by Lewis for this work), makes it seem churlish to argue with March’s choice of delivery system. Worse than churlish, it seems elitist and exclusive, a privileged bleating for canonisation of works deemed worthy by some cloistered comics in-crowd. Rich as we insiders know comics to be, they are for the most part relatively cheaply produced and easily consumed. Therein lies much of their cultural efficacy, a quality John Lewis clearly values above the literary gravitas of a hardback memoir, though doubtless nostalgia and populism have their part to play in his decision.

You mentioned comics journalism, whether such works are really comics or another form altogether, and I believe they are, though in much the same way that holy books are great doorstops. They’re capable of so much more. So, to answer your point regarding Powell’s art and the cleaner, nobler narrative he’s perhaps needlessly tasked with bringing to life, well sure the prose could have stood alone, but making March a comic was about reaching out with a message. That’s distinct from the way you and I normally approach comics, which is to read, and in reading co-create, a story.

March is a comic in the same way that the Pizza Dog issue of Hawkeye or an IKEA assembly diagram is a comic. Arguably much more pleasing, inarguably of greater import, but all three serve to tell particular versions of events, with minimal room for interpretation. John Lewis’s path into and through the Movement is the only viable one, divergent approaches evaporating the minute he rejects them.

Though this limits the reflective scope of the work, that’s fitting, for March is a history book. And like all history, March is written by the victors. That’s not to say this victory is total or final, few victories ever are. But if it is a less compelling work of art, one with less room for the reader to invest in a multitude of positions, to explore a variety of emotions, perhaps it shouldn’t surprise us, especially when the worldview it espouses has been so thoroughly vindicated.

Nat Turner promises the complexity of distorted history, events twisted by the biases of their recorders, a rebellion at its core which defies classification as victory or defeat, and if either, for which side. As you say, Elkin, March is the narrative that everyone wants, but I would argue that Nat Turner is the experience that everyone needs. Where Marchis history from the perspective of a self-satisfied present, Nat Turner is an exploration of events that, in the age of “pictures or it didn’t happen”, may as well be pre-history. Yet in being so far removed from a present owing an unclear but hefty debt, Nat Turner can strip away the rationalisation in which we clothe ourselves to reveal the same underlying humanity. In the age of drone warfare, industrialised agriculture, and tele-commuting, of systemically reinforced disconnection, Nat Turner offers us catharsis in place of reassurance. Where March tells us all will be well, Nat Turnerreminds us all was not always well, leaving us to infer the greater truth, that all will not always be well, and is not well everywhere even now. Baker invites us to live in the world of his lead without commentary or perspective on any possible worlds beyond, be they perfected futures or heavenly reward. He invites us to feel that weight, those broken bonds and cruel rebuttals, knowing that they still exist, for they are part of the human condition.

Nat Turner is present in every Bangladesh sweatshop and overheated Amazon warehouse. Yes, progress has been made, but exploitation still underpins much of the Western lifestyle, the camouflage of prejudice replaced with that of consumerist economics. Different obfuscations, same goals. Which is where works like Nat Turner come in, shining portals to a collective humanity deeper than our comfy filter bubbles, gateways to a shared inner life.

I may have gotten carried away there, Elkin, but my point is this. Lewis, by choosing to disseminate a self-referential remembrance of the mid-to-late twentieth century Civil Rights Movement, ultimately does something undemocratic. He misses the opportunity to let readers define right and wrong, victory and defeat, even good and evil, for themselves. Baker invites the reader into his imagining of a dead man’s shoes, offering freedom to interpret. In this case, the comic artist trusts his audience more than the politician, and given the topic, I find that disheartening.

Elkin: I whole-heartedly agree with your sentiment here, Lilley. Then again in most circumstances, who can you trust to tell you the truth each and every time, the politician or the artist? I'll choose the artist, each and every time. Even when they lie to you.

Maybe especially when they lie to you.

I also agree with your argument that March, by the very nature of its presentation, allows less room for the reader. And I guess, given its intent, that makes sense. Lewis has a specific story to tell about a specific moment in history with his own specific interpretation of said story. And, much like Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, this book is targeted towards an audience that may not necessarily want to tackle a lengthy prose piece, as well as, you know.... for kids. I mean, in the book the framing device is Lewis sharing his story to children for goodness sake. So it's a talking up through a talking down – which is what politicians are really good at anyway.

Baker has a different audience in mind, though, and you've pretty much outlined them already, Lilley. Yeah. It's us. By working in comics and working through comics, Baker tells the more universal tale. Just look how he chooses to endNat Turner – the story perpetuates into the next generation and then the next and then – hey look, it's you and it's me and it's the rest of the 99% trying to put words to the anger they feel, wondering how to act, eyeing the axe.

I guess I come back to my initial metaphor of protons and electrons circling the same nucleus. Perhaps we can't really compare these two books in terms of their effectiveness as they have such divergent intents. Their similar subject matter is mere coincidence. Maybe what we are looking at is the fact that comics are just another form of entertainment delivery and it is the clever creator who can tailor his or her message to whatever audience he or she wants to reach.

Maybe we've gone the long way to come to the statement, “Wow, comics are pretty cool.”

Or have I just distracted myself to the point of over-simplification?

Lilley: Not over-simplification at all, but the anticlimactic truth of good art, that “through the particular comes the universal”.

And perhaps that is the distinction here, too. Baker set out to tell a story about a man whose “sole strength was his superior brain”, to explore how a weaker minority could “dominate a physically superior majority”, and to self-publish a comic about a self-freed slave, in part as celebration for what can be learned and achieved through free access to reading.

Baker was approaching the story of Nat Turner from the point of socio-historical curiosity, but also as a personal story of a man whose actions were pivotal to a much larger and longer chain of events. It’s a particular story.

John Lewis approaches March with little concern for his own particulars. The Civil Rights Movement as depicted inMarch is both deeply personal and fundamentally, necessarily collective, with no one member’s experience privileged over any others’. What particulars of John Lewis’s life make it into March are carefully selected for their greater value as metaphor, such as the younger Lewis preaching to his chickens, tending them as a shepherd would his flock, or a Reverend his congregation, God his children.

March, if one reads the title as an imperative, crystallises before us. It is a manual for harnessing collective power for the good, an exemplar for how great battles can be won without slaughter, and it is history-proven. Nat Turner is less specific, aimed at those endlessly fascinated by the potential of the individual, the mystique of the outrider, looking to myths for inspiration.

Perhaps in preferring Nat Turner over March, we miss the point. It doesn’t matter what version of events you prefer to read, what angle of approach you take to the struggles of your time, or any other. It matters where and how you stand when you put the books down. It matters what you do.

No comments:

Post a Comment